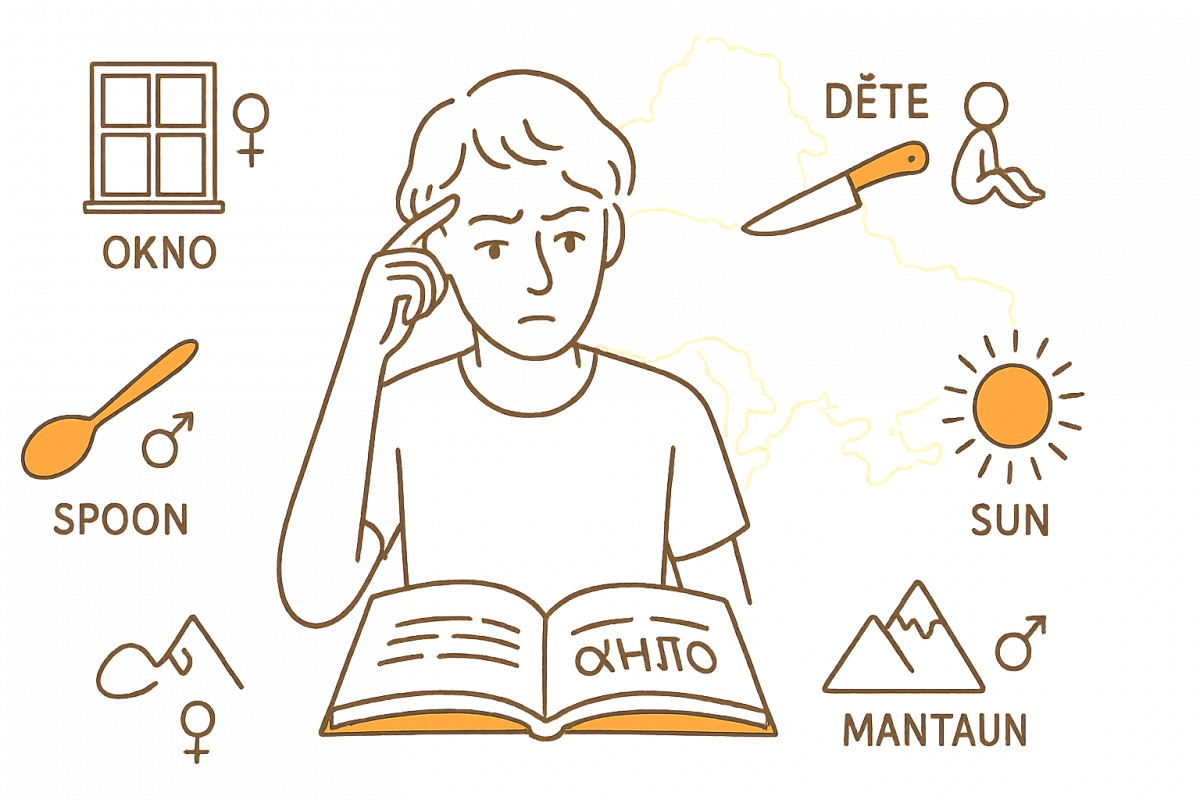

Have you ever opened a Slavic language textbook and thought, Wait… why does everything have a gender? Why is a window feminine? Why is a knife masculine? Why is a child neuter? And why do you suddenly need different words depending on whether you, personally, are male or female? If English lets you say “I’m tired” without thinking twice, why do many Slavic languages make you choose?

The moment you start learning a Slavic language, you realize you’re stepping into a worldview. But why did it end up this way?

If you ask a native speaker why “book” is feminine or why “bridge” is masculine, many will shrug. One of the first surprises learners face is how personal grammar becomes. In English, anyone can say, “I’m tired,” but in many Slavic languages, the ending of the word quietly reveals your gender. A man says one form, a woman says another. Does this mean language makes identity louder?

Then there’s the question of professions. For centuries, the word for teacher, doctor, or judge often defaulted to the masculine form. Was it because men historically held those positions? Today, feminine forms for these roles are appearing more often. What does that shift tell us? That grammar bends with society. When a language changes a title, it subtly changes the culture as well.

Look closer, and you start seeing patterns that almost feel poetic. Why is “motherland” feminine in so many Slavic languages? Why is “forest” masculine? Why is “soul” nearly always feminine, carrying centuries of spiritual weight? Are these choices random? Or are they tiny windows into how earlier generations imagined the world?

And then, right when everything feels symbolic, you learn something that makes you laugh: a child is neuter. Not because children are neutral, but because the word originally belonged to a vanished grammatical class.

But perhaps the most charming part is how each Slavic language makes slightly different decisions. Russian, Serbian, Polish, Czech, and Bulgarian often agree on gender, but they don’t always. Why is the sun masculine in one language and feminine in another? Why does a harmless noun like “bridge” switch sides as soon as you cross a border? Do these differences make languages feel like siblings who grew up together but developed their own personalities?

Gender in Slavic languages isn’t intended to confuse learners or frustrate them, even if it sometimes feels that way. It’s there because language remembers things long after people stop asking questions. Every word carries a little bit of history and a little bit of what life used to be like.

And maybe that’s the heart of it. Grammar might look dull on the page, but it often tells a story too. In Slavic languages, those details whisper about centuries of belief, tradition, and change.

So the next time you wonder why a spoon is feminine or why a mountain is masculine, pause for a moment. What if the answer isn’t about grammar at all? What if it’s simply a glimpse into how people once understood the world and how bits of that world still live on in the words we use today?